Drachenfels - A Warhammer Novel Review

Learn all about my personal high water mark for Warhammer fiction, Kim Newman's "Drachenfels." In this book, ancient evils die hard - especially when they have stage plays made about them.

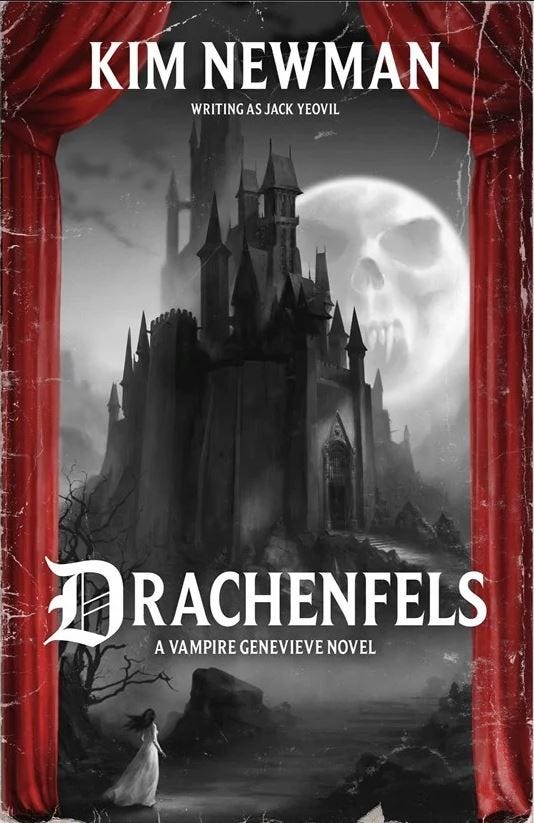

Drachenfels by Kim Newman

Published in 1989

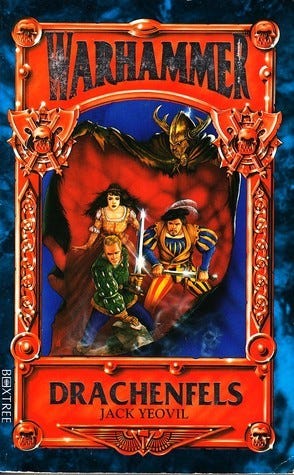

Kim Newman (writing under the pen name Jack Yeovil) set my high bar for tie-in fiction with Drachenfels. Published in 1989, it was one of the very first Warhammer Fantasy novels, released by Black Library’s short-lived predecessor, Games Workshop Books. It opens with vampire Genevieve Dieudonné and young noble Oswald von Konigswald vanquishing the millennia-old Drachenfels in the bowels of his haunted castle. Decades later, the surviving adventurers come together for a stage play based on their triumph, directed by disgraced actor and playwright Detlef Sierck. But can the power of show business match the might of Drachenfels, even after his apparent demise?

Contradicting the open-ended lore of early Warhammer Fantasy and sporting a truly novel premise compared to the decades of big-battle-obsessed “Bolter Porn” that would follow, Drachenfels nonetheless perfectly captures the feel of the setting. The book explores Warhammer Fantasy’s gothic, apocalyptic themes while presenting a convincing, functional world.

Newman is more interested in marching to his own beat, playfully echoed in Detlef’s carefree, occasionally disastrous approach to art. But Drachenfels still shows a deeper respect and understanding for the setting than I’m used to from a licensed novel.

Even if we let lore quibbles get in the way of a good story, Drachenfels makes the contradictions work in its favor by focusing on the faultiness of memory, perspective, and legend. The centuries-old Genevieve notes that the dramatization of her adventures feels more real than her memories. In that same vein, outwardly noble figures prove to be anything but, and ignoble scoundrels end up more complex than they first appear. Characters’ reputations and titles precede and shape them, from Detlef’s role as a controversial, self-obsessed playwright to Drachenfels living on through his gruesome legacy.

The book bounces between gore-dripping pulpy horror, quiet tragedy, and almost absurd comedy. The big action set pieces that define Warhammer fiction are largely eschewed in favor of smaller, more meaningful character moments. In a very meta element, Oswald’s ailing father crafts convoluted, childish battles for his “lead soldiers,” mirroring standard Warhammer narratives with a hint of mockery.

That being said, the few action sequences are well crafted and memorable, leaning heavily into Warhammer Fantasy’s core tone and themes. For all its pomp and biting wit, it’s impressive that Drachenfels never feels mean-spirited or contemptuous toward Warhammer.

All but the most exaggerated characters have personal lives and narratives enmeshed in established concepts like the Cult of Sigmar and the elector count system. Even the titular antagonist, who proves to be more myth than anything mortal, plays into that idea. A sort of proto-Nagash figure, Drachenfels’ over-the-top evil underlies a primordial, desperate character, making for one of the more compelling villains in Warhammer fiction.

Characters lead full lives, though not always the ones they hoped for, and that mundanity clashes with the fantastic foundations of their world. Some authors took a similar approach, notably William King with his Gotrek & Felix books, but Newman fully commits to the idea. We get points of view beyond the rotation of wizards, knights, witch hunters, and soldiers that dominate most Warhammer Fantasy books. And this expanded cast endures the full range of human experiences, especially long-lived immortals like Genevieve. Drachenfels doesn’t shy away from the characters’ sex lives, from sordid affairs to more genuine relationships. It fits the book’s gothic romance trappings and, thankfully, isn’t as grotesque as Ian Watson’s provocative Warhammer 40,000 books from the same “Oldhammer” era.

While usually branded as a Genivieve story and collected as such, Detlef is closer to being the protagonist of Drachenfels for most of the page count. Even so, the book leans so heavily into shifting perspectives that it’s hard to pick just one protagonist. Despite Newman’s fondness for his vampiric heroine (he would later put her into his own Anno Dracula series), she’s often more of a spectator in this debut novel. It’s another possible meta-joke, as Genivieve notes that her actual role in Drachenfels’ defeat doesn’t mesh with the legends. Even so, she plays a major part where it counts most.

Genivieve fits a lot of the “sensual vampire archetype,” but she still feels like a fully realized character with convincing flaws and a self-awareness of her immortality that makes for great reading. There’s a range of other female characters in the book, including several noble harridans I can’t help but feel are there to make Genivieve look better. Thankfully, the remaining women in the cast fulfill a variety of roles and show more depth. But in that regard – and a few other thankfully brief elements – Drachenfels reminds you that it’s almost four decades old by now. Even so, it’s important to note that one of the first Warhammer books had a female protagonist – something Warhammer as a whole struggles with to this day.

Looking at the big picture, Drachenfels is still licensed fiction, bound to its tropes and an existing IP. But I can only think of a handful of tie-in works that played their parts so knowingly or with so much passion.

Drachenfels enjoyed regular reprints throughout the years and can usually be purchased for 15 to 20 USD secondhand. It is also available in ebook format and as an unabridged audiobook.

Such a cool premise!