Gotrek and Felix: Trollslayer - A Warhammer Novel Review

The starting point for Warhammer Fantasy fiction, featuring Gotrek and Felix's earliest adventures (both the good and the bad...)

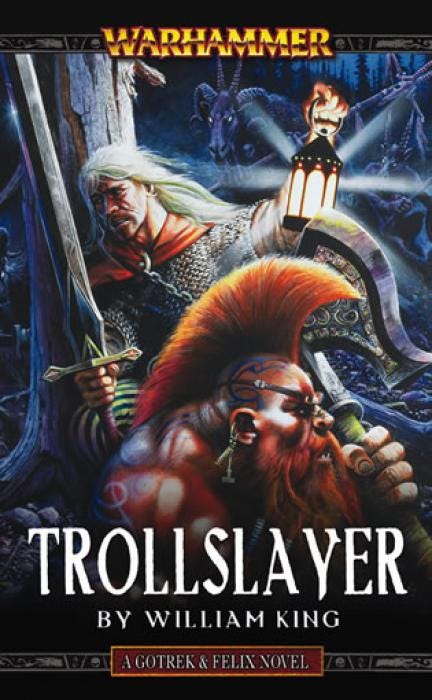

Trollslayer: A Gotrek & Felix Novel by William King

Published in 1999

It’s almost impossible for a tabletop game to have a true “protagonist.” Many of these settings focus on major established characters and metaplots, but those still offer limited perspectives on sprawling, player-driven narratives. One of the few exceptions is Warhammer Fantasy, which comes close to having “true” main characters with Gotrek and Felix. Debuting in the 1989 anthology Ignorant Armies, one of the first Warhammer books, the wandering adventurers would receive several follow-ups and a multi-novel series that ran throughout the game’s original thirty-year lifespan. Most of the early short stories, all written by series creator William King, would be collected in Trollslayer.

I would credit Gotrek and Felix’s enduring legacy to its straightforward premise, which is both distinctly Warhammer and surprisingly nuanced. Outlaw poet Felix Jaeger swears to chronicle the heroic demise of Dwarf Slayer Gotrek Gurnisson after the latter saves his life from imperial authorities. That drunken oath brings the unlikely pair all over the Old World, serving as the perfect excuse to showcase its many dark corners and strange horrors.

At a glance, there’s nothing exceptional about that dynamic, which is reminiscent of Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. But as the stories unfold the duo reveal hidden depths, particularly Felix. He’s a departure from the standard high fantasy hero and especially the typical indomitable, heavily-armored Black Library protagonist. Felix is instead a strong example of a reluctant hero, providing a grounded lens for the over-the-top grimdark of Warhammer Fantasy.

While far from helpless, the former poet is bewildered by his increasingly dark surroundings and violent behavior. King convincingly builds a sensitive, introspective character who can be selfish and even cruel when pushed. Warhammer as a whole is defined by antiheroes, so it’s refreshing to have a protagonist with admirable qualities who can be appalled by his failings.

I’d go as far as to say that Felix’s perspective, which can range from melancholic to comedic, is what makes the series work at all. It filters Warhammer Fantasy through someone who can both survive its challenges and consider the larger implications of his strange world. Almost equally engaging is the contrast that creates with Gotrek’s homicidal, death-seeking behavior.

While most of the pathos comes from Felix, the boisterous Dwarf Slayer has an air of mystique and tragedy hanging over him. Even when the point of view switches away from Felix, King never tells the story through Gotrek’s remaining eye.

That wise choice means the reader only knows as much about Gotrek as Felix does. The Dwarf’s murky history, easily-slighted pride, and violent impulsiveness make their friendship a challenging one. It generates plenty of drama and intrigue, with brief exchanges hinting that a more well-rounded person is lost beneath his suicidal oaths and the ensuing carnage.

With Gotrek’s single-mindedness, the stories in Trollslayer largely follow the same format: inglorious beginnings (usually involving detours and drinking) lead to great evils being unearthed and then gorily dispatched. It’s an approach that owes a large debt to the Sword and Sorcery genre but fortunately, King knows his way around action-packed, pulpy tales enriched by human characters. While the formula can run thin in places, it’s sturdy enough to carry a story while also leaving room for some real substance, a satisfying balance Warhammer fiction rarely strikes.

Considering Gotrek’s desire for a worthy death, it’s not surprising that Trollslayer is at its best when a memorable villain is in play. King takes full advantage of the grotesque, less uniform Chaos imagery of early Warhammer Fantasy novels to create some truly imposing antagonists. He’s one of the only authors to make “The Lost and the Damned” genuinely threatening, in part because he doesn’t let the mess of mutations stop his villains from having distinct personalities.

Once the smoke clears, it often becomes apparent that Gotrek and Felix aren’t too far removed from their warped adversaries. That recurring element adds a sense of tragedy to otherwise straightforward “hack-and-slash” tales and builds up antagonists that are much more engaging than another horde of murderous automatons.

In the stories where King pulls all of these strengths together, Trollslayer offers some of the best Warhammer fiction, specifically with Gehemneisnacht and Blood and Darkness. Unfortunately, there’s plenty of stumbling along the way. The rest of the stories have some interesting ideas and fall back on the series’ strong foundations. Otherwise, Trollslayer falls victim to King’s rapid-fire pacing and early Black Library’s short page counts. A number of the stories end up half-baked or burdened by exposition, to the point that they either feel overly rushed or sluggish and not particularly memorable. Even initially promising ones, like Dark Beneath the World adapting the iconic cover art of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay first edition, fall victim to this.

Essentially, Gotrek and Felix works when King can juxtapose relatable characters with gruesome fantasy concepts. When the reader can’t connect with those characters or if the concepts aren’t particularly interesting, Trollslayer reverts to passable Sword and Sorcery fiction. In the less effective stories, the weaker parts of King’s prose, specifically his strange repetition and cheap habit of using the threat of sexual assault to build tension, also become more obvious.

Trollslayer fully unravels in the last two stories, The Mutant Master and Children of Ulric, which are the weakest of the anthology and share the same basic premise. Gotrek is largely absent, and Felix is captured by dubiously competent Chaos cultists who aggressively monologue at him. Meanwhile, twist-based monsters lurk in the background.

These antagonists are so run of the mill that Felix comments on it, much to the dismay of the would-be villainous masterminds. And I share their concerns because it’s a bad sign when even the characters struggle to get invested in the story.

The final two stories end on anticlimactic notes, with the main physical threat unceremoniously resolved by Gotrek crashing back into the narrative. Children of Ulric’s ending is the weakest of all, abruptly concluding Trollslayer with no fanfare.

By this point, the series was in desperate need of a change, and fortunately, Gotrek and Felix got just that in Skavenslayer, the duo’s first full-length novel.

Trollslayer might represent a rocky start for Gotrek and Felix but this is still the best entry point for their adventures and Warhammer Fantasy fiction in general. Even the weaker stories sell the tone of the setting, and though certain Black Library writers have stronger prose, few match William King’s character building and grasp of the setting.

Later Gotrek and Felix stories would build up increasingly elaborate and earth-shaking plots, but there’s something truly special about this initial idea of a bickering pair having tragicomic adventures in a fallen world.

—

The Gotrek and Felix books are some of the only Black Library books that enjoy regular reprints. One of the many editions of the individual novel can be found secondhand for around MSRP and as an official eBook. Trollslayer is also collected in Gotrek & Felix: The First Omnibus, available from Black Library in eBook format.

Trollslayer also received an audiobook, excellently narrated by Johnathan Keeble.